Novel Writing Tips: Pacing

by Levi Johnson of Campfire Technology.If you’d rather watch this article than read it, you can do that here!

Pacing is one of the more elusive aspects of writing. It’s subjective, and depends pretty heavily on taste, so I can’t give you an “ULTIMATE ONE STOP GUIDE TO MASTERING PACING FOREVER AND AFTER THIS YOU WILL BE PERFECT,” but I can give you some tools to help you go back and fix a story that’s not paced right or give you some things to keep in mind as you’re writing down the line.

Now there are two different types of pacing when it comes to writing. Macro and Micro.

Macro pacing deals with overarching story elements. It asks:

How fast is the plot progressing from chapter to chapter?

Micro pacing focuses on the actual prose you are writing. It asks:

How fast is the action happening in a scene from sentence to sentence?

We can view both types of pacing as a line. The dots along it are events in the story. The closer they are, the fast the pacing, and the farther apart, the slower.

When pacing a story, these points shouldn’t be spaced evenly. They should bunch up and spread out as the story builds up and releases tension.

Where the points are bunched together things are moving fast, the constant plot progression keeps readers engaged, but when things slow down, it gives readers a break and lets them stop to smell the flowers.

There are guides out there that will help you balance where to bunch up plot points and where to spread them out. This is the idea behind Hollywood beat sheets that tell you what should be happening every page of a screenplay. We talk about that in our series on the Hero’s Journey; you can check that out here!

If you don’t want to use a pre-planned guide for pacing, then you may need to rely on your own intuition and the feedback you get from the people who proofread your story. Let’s dig in and talk about the ways you can balance each type of pacing.

Macro Pacing

The large-scale pacing can make or break your book. The key to macro-pacing is to make your audience comfortable but also a little on the edge of their seat so that they’re curious about what comes next. This means you need to balance the plot progression with downtime.A common mistake that people have is that they will have a ton of plot points at the beginning and end of their story but not as many in the middle. This can slow the progress of Act II and make the middle of the story boring, which may lose the reader’s interest.

On the other hand, sometimes you can go all gas no breaks while writing and have constant progress. This is a classic “too much of a good thing is a bad thing” moment. Never giving the audience time to relax after you build up tension can be stressful and hard to read. Having a lot of plot points in quick succession gives your reader a ton of information to process.

Readers need time to digest what you’ve given them. There should be a healthy balance of plot progression throughout the entire story. Here are some ways to help adjust your pacing.

Adjusting Pacing with Subplots

Depending on how prevalent they are, subplots have a huge effect on story pacing. They can add needed downtime from the main plotline.If your story is going lightning fast, then you may want to include a b-plot. It can be a nice detour from the major action of the plot, but don’t go crazy. Spending too much time in b-plots can make things slow and boring. Find the balance!

Two Towers is an interesting example here. If you watch the movie, Frodo and Sam’s story is told in parallel with the rest of the Fellowship, which is in line with modern pacing norms. If you read the book, though, it’s just the rest of the Fellowship for the first half, then Frodo and Sam for the second half.

I know that these are technically two separate books, but the pacing is far better in the movie. Each story takes turns and keeps you excited to see what happens when you go back to the other plot, while the book can kind of drag out when you’re reading the same story with no breaks.

That being said, I love the Lord of the Rings books and please don’t hate me for criticizing Tolkien, thanks, let’s move onto the next topic.

Cliffhangers

I know that cliffhangers can be super annoying at the end of seasons of your favorite tv show, but they are useful for switching between main plots and subplots in a novel. This may not be something as serious as “Did Glen DIE?” But you can use a type of cliffhanger to keep your audience engaged. More of a cliff question?In this video on our YouTube channel, we talked about making the audience ask questions and that’s what you want to do at the end of each section. Make the audience wonder something about what just happened that will make them want to know more, so they’re excited to continue reading.

For example, let’s say we alternate which plot we’re following each chapter. To keep your reader engaged, make them ask a question in your first chapter that doesn’t immediately get answered, then switch to your subplot in the second chapter. Then people will be excited to get back to the original plot, so they’ll keep reading.

You can do the same thing method with your subplots and back and forth.

This method keeps the reader engaged, but makes sure that they don’t get fatigued from a single plot line. Reading takes quite a bit of time and brain power so we want to do our best to keep the audience’s attention.

Subplots (but the bad kind)

Subplots aren’t always good though. You can have subplots that don’t really have a purpose. It’s important to remember that the subplot should have consequences for the main story. If it’s just an enormous waste of time, it’s going to be boring and you may lose people.If proofreaders are telling you that your story is slow, and it’s filled with subplots, it may be time to trim some of those c and d plots down a bit. This can be a problem in TV shows which are often plagued by the notorious filler episode.

There are some shows that even have websites dedicated to telling you which episodes to skip. Let’s avoid having websites tell the audience which chapters to skip with the power of good pacing and plotting.

Ask yourself: Do I have too much plot progression at this point in my story? Should I add a subplot element here?

Once you’ve identified the spots where your story goes without a major plot point for a while, that’s where you can trim down. Maybe that involves removing a single plot point from a subplot to speed things up or removing a subplot entirely. I can’t tell you what the right balance is, but I can tell you we don’t need to know every little detail of your character’s lives.

Micro Pacing

Micro pacing is one of those skills that comes with a lot of practice. You can really tell the difference between a legendary writer and a new one by how their story is paced line to line. I know I always notice when stories have great micro pacing because the reading experience is just so *chef’s kiss*.Like I said before, a lot of pacing is very subjective and comes down to taste, and that is especially true when it comes to micro pacing. Whether you like the long meandering sentences of JRR Tolkien or the more precise prose of Vonnegut, you should know what effects micro pacing has on your reader.

Adjust Scene Pacing with Sentence Length

This is one of the classic things that affects micro pacing. If your sentences are longer, then it slows down what is happening in the scene, and that’s not a bad thing. Malcolm Gladwell shared this trick in his masterclass.He talked about how brief sentences increase the pace and raise tension. It makes things happen in quick succession like in a fight scene, but to release the tension made by those machine gun sentences, he likes to end on a long sentence like a volcano building up pressure then bursting. Here’s an example.

The boy stared at the closet. A low scratching emanated from within. His heart quickened. A bead of sweat rolled down his back. He crept toward the door. Inhale. Step. Exhale. Step. Another long scratch against the wood. He lunged toward the door, grasped the knob, and tore it open to reveal the fluffy kitten trapped inside.

You can see how the tension builds up for the first couple of sentences before being released all at once with the last.

How does dialogue change pacing?

The next tool is your dialogue. There are two things to consider here, and that’s the amount of dialogue, and how it’s broken up.In some forms, dialogue can slow down the pace of a scene. If the characters are just small talking and not saying anything super important, it can strangle the pace.

Again, slowing the pace isn’t a bad thing. Maybe we want to see the characters catch their breath after an intense moment, but if you fill your dialogue with a bunch of fluff, it can bring the pace to a halt.

I can’t really tell you what’s too much and too little. Just know that playing with the amount of dialogue is a good way to change the micro-pacing.

A more concrete way to help your pacing in dialogue is to break it up with action. This is a classic screenwriting technique, but it works just as well with regular prose. Long strings of dialogue without action can get boring and lose the reader’s attention.

And when I say break up dialogue with action, I don’t mean to add a fight scene in the middle of a script. I mean tell us what the speaker is doing while they’re talking. Do they look nervous? How’s their posture? Breaking up dialogue with action helps not only keep the pace up when there’s a lot of dialogue, it also helps characterize the speaker.

Balance Descriptions to Perfect Pacing

Like I said, having a ton of dialogue can slow down the pacing, but that’s only one of the three types of text in a book. There’s also narration and description. Narration is the action and what’s happening. The more narration you include, the faster your line-by-line pace will be.

Description can act similar to dialogue. Page-long descriptions can really slow down the pace of the story. This practice is a common criticism of Epic Fantasy as a genre because it tends to take its time, and that’s not a bad thing. Like I said, it’s up to personal taste. If you don’t like slow micro pacing, that’s fine.

Also you can like both; I’m talking about it like it’s a dichotomy because it’s easier for teaching, but I really hate the all-or-nothing mentality that some people can get about writing style.

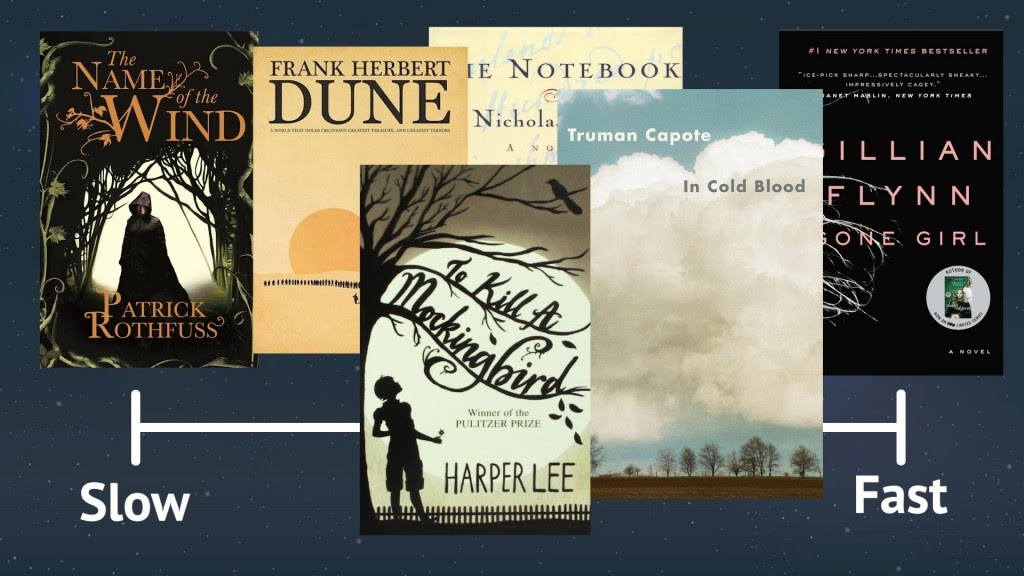

It’s a spectrum that usually aligns with genre. In fantasy you tend to find longer, more flow-y prose, while thrillers are sharper and quicker.

You can choose sides if you want to, but I like to maintain a balance when it comes to the books I read.

You can choose sides if you want to, but I like to maintain a balance when it comes to the books I read.

The goal of good pacing, is to keep your reader invested in the story. This means that your best tool for fixing and learning about your own pacing is listening to the people who read your stuff.

I will never stop saying this but having people you trust give you feedback is an invaluable resource. Fellow writers are the single most important resource to getting better at writing.

You can find more blogs and videos by Levi on the Campfire Technology website here. They also have an upcoming podcast where they workshop their own writing as well as the writing of audience members!

<< BACK to How to Write a Novel

<< BACK from Novel Writing Tips to Creative Writing Now Home